Henry Ford poses in the first car he made. In his 1922 autobiography, he wrote: “Industry will decentralize. There is no city that would be rebuilt as it is, were it destroyed – which fact is in itself a confession of our real estimate of cities. . . . The modern city has been prodigal, it is today bankrupt, and tomorrow it will cease to be.” At the time, Ford was building his vast River Rouge plant miles outside Detroit.

Frank Lloyd Wright and family escape by car to a new home in the Arizona Desert in 1928. Henry Ford had an ally in Wright, who wrote in his 1954 book, The Natural House:

When selecting a site for your house, there is always the question of how close to the city you should be and that depends on what kind of slave you are. The best thing to do is go as far as you can get. . . . The cost of transportation has been greatly decreased by way of the smaller car. In this way, decentralization has found aid, and the easier the means of egress gets to be, the further you can go out from the city. . . . Clients have asked me: “How far should we go out, Mr. Wright?” I say: “Just ten times as far as you think you ought to go.” So my suggestion would be to go just as far as you can go – and go soon and go fast.

Wright’s advice meshed with a national narrative of Americans escaping the constraints of Europe into an ever-expanding frontier. The last we hear from Huck Finn, he’s planning to “light out for the territory ahead of the rest.” The architectural historian Reyner Banham in his 1965 essay, “A Home is Not a House,” noted Americans’ preference for the outdoors over built environments, even citing the space program: “America’s monumental space is, I suppose, the great outdoors – the porch, the terrace, Whitman’s rail-laced plains, Kerouac’s infinite road, and now, the Great Up There.” The place we’ve arrived seems to say that the drama and wonder of expansion were all in the journey.

State of the Union, a series by photographer Gregg Segal poses re-enactors at Civil War battle and encampment sites that are now parking lots and subdivisions. Traveling on assignment for magazines, Segal was disturbed by America’s growing sameness: “Wherever I traveled, I’d see the same strip malls with the same Olive Gardens and Jamba Juices and Panera Breads, etc., and I wanted to say something about the erasure of the past and the homogenization of the landscape.” His images seem to ask whether this is the soul of a nation Americans fought and died for, whether we’re more the children of Abraham Lincoln or Henry Ford. What their banal settings so desperately lack can be found in the place the car first left behind: Detroit has history, variety, monumentality, significant architecture and fuel for the imagination.

Henry Ford’s 1904 Ford Piquette Plant may be Detroit’s, and America’s, most influential building; not for its own style, which is that of a nineteenth-century textile mill, but for the suburban world of malls, office parks and subdivisons it spawned, a nation of car-secondary landscapes and buildings. It was the first factory built by Ford and the birthplace of the Model T, which made car-ownership affordable to the average American and put the nation on wheels. The Piquette Avenue Industrial Historic District recognizes the significance of this building and its neighbors, early car plants that still employed 50,000 workers as recently as the 1950s when Detroit’s population peaked at 1.8 million. Today, Detroit’s population is back to its pre-Ford 700,000.

Two blocks up Piquette Avenue, architect Albert Kahn’s 1921 Fisher Body Plant stands unrestored. The seven Fisher brothers’ company developed enclosed car bodies, adapting the automobile from fair weather touring vehicle to everyday transportation. Kahn is sometimes called the builder of Detroit for his many and often huge projects in the city, including the Packard Plant, now one of Detroit’s signature ruins. It’s as hard to begrudge the Fisher Plant’s evocative decay as the colorful nature erupting through the sidewalk nearby. Detroit offers many such opportunities to experience the sublime; not chocolate cake sublime but Romantic Movement sublime, the pleasurable terror felt in the face of dwarfing enormity and nature’s mortality-mocking permanence. Add the pathos, mystery and picturesque decay, and it’s a strong brew. Detroit is now world famous for its much-photographed ruins. Rather than demolish them, the city might exploit their potential to stimulate tourism.

Unlike the red brick Ford Piquette Plant, Kahn’s Fisher Plant is stripped of all conventional architectural decorum. He had begun using reinforced concrete to this then-radical effect in his 1905 design for Detroit’s Packard Plant. Called “daylight factories” for their naturally-lit work floors, these buildings maximized windows and open interior space, paring structure to a minimum and pushing the limits of functionalism. Their exposed concrete structural frames weren’t hidden under the sort of brick or stone skin into which stylizing architects would typically invest much of their effort, often to simulate a Renaissance palazzo or other borrowed model. In Kahn’s industrial buildings, structure and skin were one, function was honestly expressed, integrity trumped artifice, and a powerful purity of form emerged. As Reyner Banham detailed in his book, A Concrete Atlantis, European architects were influenced by grainy photos of just such American factories in trade publications. Le Corbusier’s seminal 1923 book, Towards a New Architecture, reproduced these photos and held American factories up as models. The honest qualities of Kahn’s plants would become articles of faith for modern architecture from the Bauhaus through the International Style and to this day. The source of this DNA lies scattered among the ruins of Detroit. If the Bauhaus could design its Dessau school in imitation of a daylight factory, might not Albert Kahn’s factories one day house design schools?

For all its famed blight, this too is Detroit. The 1928 Fisher Building, “Detroit’s largest art object,” was a real estate investment of the Fisher brothers of “Body by Fisher” fame after they sold most of their coach works interest to GM for staggering sums. It was designed by architect Joseph Nathaniel French, working within Albert Kahn’s office. Despite Kahn’s role in launching architecture’s unornamented modern movement, he did not consider himself a modernist and held that non-utilitarian buildings should be decorated. It’s tempting to envision the Fisher Building’s spectacular lobby used, like Milan’s Galleria, as a public living room.

The lobby of Detroit’s 1929 Guardian Building is a fanfare for the common office worker.

Designed by architect Wirt C. Rowland, The Guardian Building is the sort of exuberant jazz-age skyscraper that largely defines older American skylines. The 1920s building boom coincided with Art Deco’s moment and was followed by a construction drought that lasted through decades of depression and war, leaving the style distinctly the face of the modern American city in its unbridled youth. Detroit has examples of national importance.

Glass-faced row houses designed by Mies van der Rohe look out on a nature in Detroit’s Lafayette Park. Most architects would be surprised to learn that Detroit has in this project the world’s largest collection of buildings by Mies, one of the profession’s two or three most revered twentieth-century practitioners. Lafayette Park is also considered the major built work of urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, who had earlier taught at the Bauhaus under Mies’s leadership. Mies closed the Bauhaus in 1933 rather than capitulate to Nazi demands for the removal of Hilberseimer and another left-wing teacher, the painter Wassily Kandinsky. Lafayette Park is a rare case of highly successful urban renewal; a vibrant, affordable community with a low vacancy rate more than a half century after its completion. (A renovated 1400 square foot three-bedroom row house was advertised earlier this year for $159,000.) The 2012 book, Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies, looks at Lafayette Park through the lives and words of its residents, with many photos of the maximized social freedom and variety of living allowed by Mies’s less-is-more minimalism. Residents range from one who has never heard of Mies (“Is he a good architect?”) to one who can describe in detail the personal and professional relationships between Mies and his collaborators on the project. All praise Mies’s open sense of space. Lafayette Park’s presence in Albert Kahn’s Detroit is poetic justice. From the 1940s on, Mies’s work was strongly influenced by Kahn’s steel-framed industrial buildings.

As recorded by Kahn scholar Grant Hildebrand, Mies’s student Myron Goldsmith recalled him poring over the designer George Nelson’s recent book on Kahn’s work in 1940. Mies had immigrated to America in 1938 to head the Department of Architecture at the Armour Institute, now Illinois Institute of Technology. His chief assistant at the time, Gene Summers, has said Mies “was particularly impressed with the automotive architect-builder in Detroit by the name of Albert Kahn.” By this time, Kahn had moved from his pioneering use of reinforced concrete to working with steel structure, and he was about to send a second wave of influence through modern architecture.

Resemblance alone speaks for Kahn’s impact on Mies. At left, Kahn’s extension to the La Grange Diesel Plant, as pictured in George Nelson’s book, closely prefigures Mies’s 1943 IIT Minerals and Metals Building, at right, his first construction in America. Mies’s work from then on, including such iconic buildings as the Farnsworth House and the Seagram Building, would be rooted in the crystalline, steel-structure vocabulary of Kahn’s factories. Lafayette Park’s low-rise buildings in fact look more like a Kahn plant than conventional row houses. Kahn, who believed his stripped-down style was only suited to industrial buildings, would not have approved.

Kahn would have been appalled at this collage by Mies and his students. It appropriates a photo of Kahn’s Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Plant from George Nelson’s book, inserting a concert hall. The image argues for Mies’s concept of universal space, liberated for any use by structurally unimpeded expanse and the absence of a use-specific received style. The idea is innately sustainable; neutral, flexible buildings are readily adapted to new uses when they outlive their original ones. As a bonus, architecture breaks free of any one prescribed use, reclaiming the timelessness and autonomy of ancient monuments. Mies’s collage seems uncannily pertinent to Detroit, an entire city awaiting new use, rich with vacant factory floors, many by Albert Kahn. Proving the viability of former industrial plants as cultural settings, the Dia Art Foundation’s collection has been based in a quarter-million square-foot 1929 Nabisco box printing factory in Beacon, New York, since 2003. The vast industrial setting is a critical part of the experience of the museum, helping justify an 80-minute train ride from New York City. Something similar in Detroit could add to the role of the venerable Detroit Institute of Arts in making the city an art destination.

One Woodward Avenue, completed in 1963, was the first skyscraper designed by Detroit-based Minoru Yamasaki. Although he is most famous for designing New York’s World Trade Center, Yamasaki’s Detroit work has a better relationship of detail to overall scale. When America started building again after World War II, it was as a grown-up world power donning sober International Style architecture. Yamasaki provided an alternative, enlivened with decorative historical and regional influences: “There must be elements of delight, to offset the monotony of mass-produced building and to enhance the enjoyment of life.” This personal inflection keeps his Detroit buildings looking fresh today, amid their now often bland-looking International Style contemporaries.

Yamasaki’s 1964 DeRoy Auditorium at Detroit’s Wayne State University rises to a crescendo of pointed arches. The Auditorium’s top-heavy design should be balanced by its reflection in the now empty reflecting pool, itself an emblem of Detroit’s troubles. Until it’s refilled, Yamasaki’s whole is less than the sum of its parts. In fact, its only half its parts. The building shows the influence of Islamic architecture which Yamasaki first adopted for his design of the 1961 Dhahran Air Terminal Building in Saudi Arabia.

Inside the DeRoy Auditorium, the lines of Yamasaki’s stair railing sketch the base of his World Trade Center towers to come. In a 2001 Slate piece, architect Laurie Kerr makes much of the towers’ implied pointed arches and Yamasaki’s description of the plaza between them as a “mecca.” She argues that the Saudi Binladen Group would have had a hand in his several Arabian projects and that Osama Bin Laden “must have seen how Yamasaki had clothed the World Trade Center, a monument of Western capitalism, in the raiment of Islamic spirituality.”

With a manufacturing history dating to well before Henry Ford, Detroit has a wealth of anonymous but architecturally interesting industrial buildings that might serve art as well as industry.

A city street through a neighborhood of disappeared houses evokes a country lane. Much of Detroit now looks like this, as if to prove Henry Ford’s prediction that cities will cease to be. This photo’s belatedly replaced sidewalk corner responds to a court order that Detroit honor curb ramp requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Blocks like this are a new kind of introduction of nature into a city; not encapsulated, planned parks but swaths of green randomly marbled through the urban fabric. They might remain as a surreal cocktail of city and wilderness, or be made laboratories for experimental forms of housing supported by existing infrastructure.

Detroit presents the spectacle of a major American city returning to nature.

Piranesi’s etchings of tree-sprouting Roman ruins come to mind.

A brick house with graceful tile and stone begs to be restored. Its new roof and brickwork may buy it some time.

Tyree Guyton returned from military service to find that his old neighborhood looked like “a bomb went off.” He and his grandfather Sam Mackey began making art from abandoned houses on Heidelberg Street in 1986. Although some of the houses have been lost to arson, the Heidelberg Project continues to be an attraction and source of local pride. The attention has made the area a safer place for its residents.

Carl Nielbock came from Germany to discover his roots in Detroit, the home of his black G.I. father, and stayed. A sign outside his ornamental metalwork company, C.A.N. Art Handworks, demonstrates its stock in trade while celebrating the city whose architectural heritage the business helps restore. Unsanctioned expressions like this sign, the Heidelberg Project and Detroit’s other outdoor art installations are in the American spirit of Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, a national landmark. These works and the efforts of those who take it upon themselves to mow the city’s neglected parks or prune its trees give one hope for Detroit.

A brick house in Detroit’ historic Corktown neighborhood is scratched with names and initials of those who waited at an adjacent streetcar stop, some of whom have returned to update their entries. The architectural visionary Lebbeus Woods wrote in his book Radical Reconstruction that “the complexity of buildings, streets and cities, built up over time and across the span of innumerable lives, can never be replaced.” The book’s words and illustrations propose an alternative to demolition, which destroys the past, and restoration, which denies history’s failures and reinstates the old order to blame for them. Woods’ chosen principle “to create the new from the damaged old” would be well applied to Detroit. The city’s historic resonance is not only irreplaceable but unavailable to competing suburban developers or practitioners of New Urbanism.

The inscribed brick house stands on a graceful, leafy block of Bagley Avenue. Henry Ford built his first car in a backyard coal shed on the street.

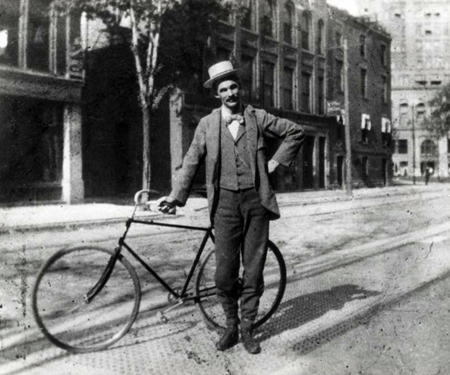

Ford poses with his bike in 1893. The 1890s saw the greatest boom ever in bicycle popularity, a craze boosted by technological improvements including inflatable tires. In 1896, Ford built his first car, outfitting it with bicycle tires and calling it the Quadricycle. A new boom was born. Ford’s insistence that the city would disappear made good business sense. Cities, after all, were negotiable by streetcar or bicycle. General Motors notoriously bought and decommissioned many American cities’ streetcar systems in the 1950s. This is known either as “streetcar conspiracy” or “streetcar conspiracy myth,” depending entirely on your politics. Detroit’s streetcars were sold to Mexico City, still in good enough shape to serve there for another thirty years.

Bicycles ply the Dequindre Cut, overlooked by graffitti art and one of Mies van der Rohe’s Lafayette Park Towers. Opened in 2009, the recreational greenway was converted from a rail line originally cut into the ground to pass below crossing streets.

Streets and car traffic pass above the Dequindre Cut’s cyclists and pedestrians. Historically, industrial routes similarly avoided public streets. The Australian architectural educator and bike planner Steven Fleming, in his 2012 book, Cycle Space, notes the potential of abandoned industrial rail lines and waterways, often overlaid or skirted by the public streets of later civic development, to be sewn together into vast networks of bike paths: “As a cyclist, I see parallel cities coming into focus, on industrial land, with their backs turned on those places where people drive.” The car-free streets of Detroit’s vacated residential blocks could add to the city’s brownfields as a canvas for such a bike network. Detroit’s less-than-walkable density puts it in a prime position to benefit from the kind of bike system Fleming envisions. This is a more important priority than it might at first seem, one with implications for job growth. Even in oil-invested, red-state Texas, major cities are creating bike lanes and bike share programs. Robin Stallings, head of the bike advocacy group Bike Texas has said: “Companies like Samsung and Google are looking at the bicycle facility infrastructure before they decide what city they’re going to locate in. So this is really being driven by economics in Texas. It’s not all about people seeing themselves on a bicycle, but seeing what it does for the quality of life in a city.” As Frank Lloyd Wright used to say (without crediting Dorothy Parker): “Take care of the luxuries and the necessities will take care of themselves.”

Henry Ford argued that we’d never rebuild cities as they are. Would we accept the automobile as a new invention today? Today’s safety standards, environmental awareness, and appreciation of the social and cultural benefits of density say no. As ethicist Randy Cohen has noted: “If you introduced a transportation system in the U.S. by declaring: ‘It’ll slaughter 30,000 people a year and hospitalize ten times that number,’ it’s hard to believe it would catch on.” We tolerate cars because the world they’ve created over the course of a century requires them. Facebook and smartphones notwithstanding, our lives are built on the platform of Ford’s dirty and dangerous late nineteenth-century technology. Cars have certainly evolved, but even electric ones are charged by fossil fuel, and they won’t make a nation of paved sprawl more sustainable.

The car wasn’t even universally embraced in Ford’s day. Technology historian Peter Norton points out that the introduction of cars to cities in particular met strong public resistance, forcing the industry to fight back; when the public branded fast drivers “joy riders,” car interests coined “jay walkers” to shift blame for street carnage onto pedestrians. Norton also notes that “America’s love affair with the car” was no one’s spontaneous observation, but a promotional catchphrase seeded in 1960s television. Auto makers and oil interests depended heavily on New York’s Robert Moses and his acolytes nationwide to muscle cities into car deference. New York’s 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs, run by Moses, were largely auto industry ads for a car-based world of tomorrow. Jane Jacobs’ resistance to Moses took her from neighborhood activist to national icon. Their streets-for-cars versus streets-for-people battle, billed as the central drama of urban planning, is now slated for operatic treatment.

Detroit is a telltale worth watching. As the birthplace of the car, it was first to suffer from Ford’s dream of a post-urban America. By rights, it should be first in line to become a new kind of post-Ford American city. A new streetcar line is already in construction. If there’s an afterlife for Detroit, there may be for Buffalo and other American cities loaded with our history and architectural heritage.

American cities aren’t the places to flee they once were. The sooty, overcrowded metropolis of Henry Ford’s day is now a thing of China, where people are as desperate to own cars as we once were. Americans are less shackled to cities by jobs and more likely to live in them by choice. Vishaan Chakrabarti’s compellingly illustrated 2013 book, A Country of Cities, makes an overwhelming case for the personal and national benefits of re-urbanization, a trend that he notes is already under way. The greater the number of Americans who live in cities, the healthier and wealthier we’ll all be, even those of us who don’t choose the urban option. This, and everything else Detroit has to offer, make its fate a national concern.

A wooden street lamp pointed out near the Fisher Body Plant is a small part of Detroit’s irreplaceable authenticity. This ArchiTakes post and one to follow, on Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, are the product of a single 25-mile bike tour generously hosted by the author of the blog, One More Spoke, and his ebullient fiancée. Their love of Detroit, despite its hardships, was infectious. But for a missing section of pedestrian overpass handrail likely lost to scavengers, no part of the tour felt unsafe. People in Detroit greet each other when they pass. Anyone who doesn’t is assumed to be visiting from New York.

Next up: Detroit’s Grand Central