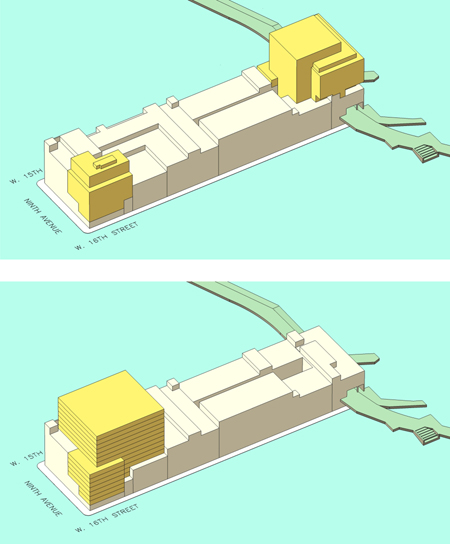

Shown in gold at top are Jamestown Properties’ proposed additions to Chelsea Market: 90,000 square feet at Ninth Avenue and 240,000 square feet at Tenth Avenue above the High Line, which is shown in green. Below is what Jamestown’s proposal might look like, give or take a floor, if it were really about needed office space and not about raiding the High Line’s light, air and sky views. Call it Scheme B. Either option would require a zoning change to increase Chelsea Market’s floor area by 330,000 square feet, but Jamestown’s would need a zoning change that would perversely allow construction within the footprint of a public park. City approval of Jamestown’s proposal is nonetheless thought to be a done deal.

There’s no reason to build above the historic market complex at all when there are vacant and underdeveloped lots right across 15th Street, and when Hudson Yards – just 14 blocks to the north – is zoned for 26 million square feet of new office space. Scheme B is submitted only to expose how far Jamestown is bending over backward to seize High Line open space from park-goers. Scheme B would add onto only the east end of Chelsea Market, completing the street wall above the one-story Buddakan Restaurant, and setting back at the level of the existing Ninth Avenue cornice line and existing side street rooflines.

Scheme B has these advantages:

New office space would be closer to subway lines and Google’s new headquarters across Ninth Avenue

Construction wouldn’t be inefficiently split between sites at opposite ends of an 800-foot long block

None of the new construction would be built over the interior court that now brings natural light to Chelsea Market’s retail concourse

The cost of cantilevering part of a tower over the High Line would be avoided

No appreciable shadows would be cast on the High Line, and it wouldn’t be robbed of light and air

The shape of Chelsea Market’s neighboring Caledonia apartment building, sculpted by zoning to step down to the existing height of Chelsea Market at Tenth Avenue, wouldn’t become a multimillion dollar irrelevancy

Scheme B would provide all the dubious benefits – none of which actually warrants a zoning change – which Jamestown claims for its own scheme: creating jobs, letting current tenants grow in place, and increasing customer traffic for Chelsea Market’s retailers. The High Line would still get its full payout from Jamestown, a contribution of about $19 million dollars, from a formula based on the total square footage of the building addition.

Scheme B would also respect Jamestown’s phony case that its proposal spares mid-block character by directing area toward the avenues. Even if Chelsea Market had a low-rise mid-block context rather than a 25-story housing project on one side and hulking loft buildings on the other, avoiding the middle of the block to build over a park is like swerving to miss a dog and running over its owner.

Clearly, something other than responsible urban planning is behind the city’s certification of Jamestown’s proposal, which is consistently based on such ridiculous and plainly self-serving arguments. Everything points to a back room deal between a few key players:

Robert Hammond, co-founder and president of Friends of the High Line, is apparently desperate for the $19 million Jamestown would pay into a High Line maintenance fund in return for the floor area bonus it needs to add onto Chelsea Market. This follows on his failed effort to have the community close the gap in the park’s operating costs with a tax on those living near the High Line. Hammond is now reduced to letting an opportunistic Jamestown gouge the park and the community just to keep the High Line in fresh paint. His support for Jamestown’s proposal gives it all the credibility – and perhaps all the viability – it has. If this is his financial plan for the park, one has to wonder how long it’ll be until the next fire sale.

Amanda Burden, the City Planning Commission chair, must surely view the High Line as a major piece of her legacy. She may so identify Hammond with the park as to deem its resources his to parlay. This would be a big assumption, given that $112.2 million in city funding and $20.3 million from the federal government built most of the park, according to the New York City Economic Development Corporation’s website. The High Line open space Jamestown would privatize and cash in on was enriched with tax dollars as part of a public process intended to create a park.

Jamestown Properties sold Google its new headquarters, the full-block building at 111 Eighth Avenue, for $1.9 billion and then bought out its partners in ownership of Chelsea Market, where Google also has offices, across Ninth Avenue. Jamestown, first and foremost an investment firm, would have a gold mine in space over the High Line that might be turned into office floors with views up and down New York’s hottest new attraction and over the Hudson. It has a ready, deep-pocketed tenant in Google. Jamestown’s promotional material suggests that its tenant needs more space: “As Google looks to occupy 100% of 111 Eighth Avenue, and Chelsea Market’s office floors remain fully leased, Jamestown is looking to capture the neighborhood’s dynamic growth and ensure that current Chelsea Market tenants have the option to grow within the complex.” Jamestown’s frequent reference to an emerging multi-block “technology corridor” might well be code for a Google campus stretching from Eighth Avenue to the Hudson.

Google is the 800-pound gorilla in Chelsea. When Sergey Brin cut the ribbon on his company’s new Chelsea Market offices in 2008, he shared scissors with no less than Senator Chuck Schumer. Google is catnip to politicians, especially the tech-smitten Bloomberg administration. As reported in a recent New York Times article by David Chen about Jamestown’s plans:

A Bloomberg spokeswoman, Julie Wood, called the proposal “an important economic development project,” saying it would prompt additional development along the High Line, and attract more technology firms to a neighborhood that is already home to Google’s New York City headquarters and that will be the temporary home of Cornell’s new applied sciences school.

Google might not only afford the top-dollar rent on space above the High Line, but use views from it to further its well known practice of luring talent with perks.

Don’t look for the City Planning Commission to reshape Jamestown’s proposal into anything like Scheme B. Clearly, responsible zoning isn’t the issue. There’s every appearance that the deal, from the start, has been about selling off a prime piece of High Line open space. If not, why would City Planning even have certified Jamestown’s proposal to build above the park? Powerful parties get what they want. Anyone naïve enough to ask whatever happened to democracy gets a horse laugh.

If Google’s name opened doors for this, it doesn’t paint a pretty picture: city government complicit in taking a public amenity from its people to dangle before a private corporation it holds in higher regard. Google wouldn’t have to do any evil to get its private High Line skybox. That would all be taken care of. If memory serves, when a corporation threatened to leave the city unless it got a tax break in the 1980s, Mayor Koch replied: “Go ahead. When you leave New York, you’re going nowhere.” If this city isn’t a big enough draw for Google, our leaders shouldn’t respond by making it less attractive to everyone else.

Technically, Jamestown’s proposal is still in the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, known by the dyspeptic acronym, ULURP. In practice, the review process is a charade of public participation, a rigged game serving mainly to dignify deals already sealed by the time the “review process” is triggered by City Planning certification. As proof, only one project in memory has been certified but not built: a redevelopment of the Bronx’s Kingsbridge Armory, rejected in 2009 under atypical circumstances. Although local community boards get to weigh in on projects during ULURP, resignation reigns. Board members feel that if they flatly oppose a project, it will get built anyway and they’ll lose a place at the table to bargain for concessions or offsets, so they vote “no, unless” or “yes, if” concessions are made. These typically amount to side deals, like Community Board 4’s vote to reject Jamestown’s plan unless off-site affordable housing is provided. This vote opened the door for Chelsea’s City Council Member, Council Speaker Christine Quinn, to support the proposal without overruling a flat “no” vote by her board. Speaker Quinn is the only one whose vote can now kill Jamestown’s proposal. Chelsea residents feel betrayed by their Community Board’s vote and are outraged at having their neighborhood made more like Times Square to benefit the High Line and corporate fat cats. Speaker Quinn is caught between responsibility to her constituents and a pro-business stance essential to her campaign for mayor. Maybe there’s a third way: vote against Jamestown’s proposal without conditions, pointing to solid land-use reasons and the many ways in which Jamestown’s proposal is egregious, deceptive and predatory. It’s not like there’s any lack of evidence. Is no business bad enough that opposing it would mean Quinn is anti-business? Would she rather be known for betraying her constituents and letting rich corporations pillage the public realm?

This photo shows how the high-rise Caledonia apartment building was sculpted by Special West Chelsea District zoning to keep its tower portion away from Chelsea Market, seen to the right across 16th Street, and step down to the historic market complex where the High Line passes through it. Jamestown now plans to build above Chelsea Market, undoing this planned and expensively executed piece of sky exposure. The Caledonia was already under construction when the Special District was created, so it inherited rights to greater height than nearby sites under the Special District’s new High-Line-focused zoning. Nonetheless, Jamestown has cited the Caledonia’s height as justification for its own addition, effectively claiming its neighbor’s grandfathered air rights.

The Caledonia was one of only three sites within the Special District eligible for its zoning’s High Line Improvement Bonus, which allows additional building area “granted in exchange for a monetary contribution for the restoration and development of open space on the High Line, both on and adjacent to these sites.” The three sites had special potential to create open space, including the yet-to-be-built 18th Street Plaza component of the High Line. Two of the sites were, and remain, unbuilt. The High Line Improvement Bonus was never meant to allow expansion of completed buildings, but to cultivate park-enhancing open space on undeveloped sites, or an incomplete one, in the case of the Caledonia. The building’s tower was held away from Chelsea Market and 16th Street, where it would “in combination with the very high streetwall of the Chelsea Market Building on the south side of 16th Street compromise the pedestrian experience,” according to the Special District’s zoning text. Jamestown proposes to have the Special District and its zoning extended to include Chelsea Market, claiming that this would qualify it for the same High Line Improvement Bonus applied to the Caledonia for a very different and site-specific purpose. Jamestown’s promotional material distorts the Improvement Bonus into a standard feature of the Special District: “As part of the provisions set forth by the [Special West Chelsea District zoning] amendment, properties adjacent to the High Line were eligible to receive elevated Floor Area Ratio (FAR) allowances.” So much for the scalpel-like Special District zoning that helped make the High Line such a successful design. As dumbed down for exploitation by Jamestown, the High Line Improvement Bonus isn’t a tool for development of open space, but for privately appropriating it. The High Line open space already earned and shaped by the Improvement Bonus from the Caledonia’s developers, in exchange for their right to build bigger, will be made meaningless by Jamestown’s addition of a tower nearly as tall as the Caledonia’s right across 16th Street. Jamestown merely lays claim to the right to build bigger because the city let the guys next door do it. (And what of the next guys to come along?) This is a notable betrayal; the Improvement Bonus is the only point of contact, and a nominal one at that, between Jamestown’s self-generated zoning rationale and the provisions of the Special District that Chelsea Market would join in name only. Jamestown’s proposal otherwise ignores the aims of the Special District and spits in the face of its stated purpose, “to ensure that light, air and views are preserved along the proposed High Line open space.”

The Chelsea Market zoning debacle points to a broken city review process that should be a political campaign issue unto itself. It’s a stated priority for Julie Menin, the former Community Board 1 chair and presumptive Manhattan Borough President candidate. Menin told ArchiTakes that “ULURP needs to be reformed” and that the outcome of the review process “shouldn’t be a negotiated settlement every time.”

Meanwhile, Save Chelsea is leading the effort to stop Jamestown’s zoning travesty.

More on Chelsea Market:

The Chelsea Market Deal, brought to you by ULURP – November 4, 2012

High Noon at Chelsea Market – March 20, 2012

Jamestown’s Shady Plan for Chelsea Market – November 22, 2011

What New Zoning Could Mean for Chelsea Market – May 31, 2011

Saving Chelsea Market – March 22, 2011

Terrific job of covering this unfortunate plan!

A foul taste in my mouth. Awesome write-up nevertheless. Wish you posted more often!