Last Sunday’s sunshine made the High Line’s “Tenth Avenue Square” a pleasant place to relax, even in late November. The popular grandstand feature would be cast into shadow at the hour this photo was taken if Jamestown Properties builds its planned office tower over Chelsea Market. The effect would be particularly damaging to a park highlight meant for lingering rather than strolling.

Designed by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the High Line is more than a critical and popular phenomenon. It’s one of New York’s most successful large-scale design initiatives since Rockefeller Center. In an era when any visionary large project is almost impossible to coordinate and execute, the High Line is nothing short of miraculous. Certainly, all that separates it from designated landmark status is the minimum required passage of time. The park is not only the work of talented private sector firms, but of the Department of City Planning, which created a Special West Chelsea Zoning District around the High Line intended “to ensure that light, air and views are preserved along the proposed High Line open space.” These words are so central to the Special District’s purpose that they appear as often as twice per page in its zoning text. As anyone who’s walked the High Line knows, light, space and sky are to its elevated structure what grass and trees are to Central Park’s paths. The open space carved out by the Special District’s zoning is of a single design with the High Line. To change it would be to alter a landmark.

Jamestown Properties proposes to have Chelsea Market brought into the Special West Chelsea District as a mechanism to allow addition of a third of a million square feet above Chelsea Market, a result that couldn’t be more hostile to the Special Disrict’s purpose. As the real estate investment fund company that owns Chelsea Market, Jamestown would interpret the Special District’s provisions to its own ends, primarily to build a high-rise tower above the High Line and cash in on its top-dollar views. A key piece of Jamestown’s zoning strategy is its claim that Chelsea Market is entitled to the specific zoning provisions granted the site of the Caledonia apartment building just across 16th Street, apparently on the simplistic grounds that what’s good for one block must be good for the next. Let’s take a look.

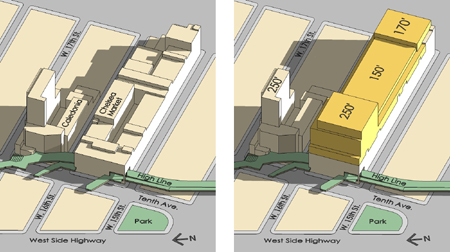

The image at left shows the Caledonia apartment building and across 16th Street, Chelsea Market in its current form. The Caledonia was deliberately shaped by Special District zoning to step down toward the High Line and the historic Market complex just outside the District. At right, in gold, is the new zoning envelope Jamestown has proposed for Chelsea Market once it’s included in the Special District. Jamestown proposes to fill most of this envelope’s 250-foot tall volume at the Tenth Avenue end of the Market with an office tower that would make the zoning-sculpted form of the very substantial Caledonia irrelevant and cast part of the High Line into shadow, particularly at mid-day during the colder months of the year. The park’s Tenth Avenue Square grandstand feature is seen to the lower left of the Caledonia in these images.

The Caledonia is a linchpin for any evaluation of Jamestown’s proposal on urban planning merits. Occupying the southernmost lot in the Special West Chelsea District, it appears in the lower left corner of this model of the District from the Department of City Planning website. Chelsea Market is seen to its left in white, under “16th St,” along with a glimpse of the green High Line crossing Tenth Avenue. The District customizes zoning to surrounding streetscapes and to the High Line on the blocks over which it passes from 16th to 30th Streets. Lower heights are allowed within the District where it approaches the lower-scale Chelsea Historic District, seen in white to the left of 23rd Street. Higher buildings are allowed farther away from historic buildings and to the north, where the District approaches the anticipated high-rise development of the Hudson Yards. The Caledonia’s considerable height is an exception, allowed only because the building was already in construction under earlier, higher zoning when the Special District was created in 2005. The Department of City Planning nonetheless engaged the Caledonia in the Special District, shaping its unfinished form to complement the High Line. Despite its unusual height, the Caledonia was stepped down in a way that’s consistent with the lower heights allowed throughout the Special District for lots near the the High Line or historic areas. In addition to protecting High Line open space, a stated goal of the Special District zoning is to “provide a transition to the lower-scale” surrounding historic architecture of Chelsea. Completion of both the Caledonia and this section of the High Line has realized this goal. Jamestown’s proposal would undo its achievement.

After considering a maximum height of 220 feet for the Caledonia’s lot, the City Planning Commission allowed 250 feet expressly so the project could realize its full zoning area, mainly in a higher tower away from Chelsea Market, and still step down to a contextual “base” of 120 feet near the High Line and Chelsea Market. The Special District zoning text states:

“The Commission believes that the proposed base height of 120 feet adjacent to the High Line is appropriate and is consistent with the loft buildings that occupy the other three corners of the West 16th Street intersection with Tenth Avenue. At the same time, the Commission believes that an addition to the base height along West 16th Street would, in combination with the very high streetwall of the Chelsea Market Building on the south side of 16th Street, compromise the pedestrian experience. The Commission therefore accepts the modification that would establish the maximum building height of 250 feet within Subarea I.”

Although the Caledonia’s great height was effectively grandfathered from previous zoning six years ago, Jamestown would now exploit it as a precedent, reaching back through time to make a grab for the taller zoning the Caledonia had before there ever was a High Line or a Special West Chelsea District. The zoning text allowed the Caledonia to be 250 feet high so it could build that tall on the side away from Chelsea Market and step down to “optimize conditions on the High Line and along West 16th Street.” It says everything about the merits of Jamestown’s proposal that it would put this height on top of Chelsea Market.

The Special District’s summary of aims emphasizes residential and arts-related uses, addresses new buildings, and calls for relating to and enhancing neighborhood character and High Line open space.

Jamestown presented its own list of “zoning goals” to Community Board 4 in March. The latter two point a “but you let them” finger at the Caledonia. The first two, “directing floor area toward the avenues” and “establishing lower heights on the mid-block to protect character” are could-be-anywhere strategies that ignore the very existence of the High Line, much less the Special District’s prioritization of it. Jamestown’s Michael Phillips was still talking these up in an interview printed by Chelsea Now earlier this month. Phillips told the paper that the proposal provides: “Protection of the middle of the block, which in conventional wisdom today protects light in the air and it’s low and you put the height at the end and essentially you get better street light down the middle of the block.”

Phillips didn’t say why Jamestown would direct disproportionate bulk toward Tenth Avenue, above the High Line, where it would just incidentally have lucrative views. Arguing against Jamestown’s “conventional wisdom” rationale, the Special (not conventional) District contains a High Line Transfer Corridor, from 19th to 30th Streets, “intended to enable the transfer of development rights from properties over which . . . the High Line passes and thereby permit light and air to penetrate to the High Line and preserve and create view corridors from the High Line bed.”

As illustrated on the Department of City Planning website, the High Line Transfer Corridor is at odds with Jamestown’s piling-on of bulk above the High Line. If this image doesn’t clearly enough show the poor fit of Jamestown’s plans with the Special District’s priorities, the zoning text expressly requires that “the High Line shall remain open and unobstructed from the High Line bed to the sky . . .” Jamestown can be expected to claim exemption from this on the grounds that Chelsea Market itself already passes above the High Line, but the provision clearly aims to protect High Line visitors’ views to the sky from just what Jamestown would build.

A rendering from Jamestown’s website shows its planned addition above Chelsea Market. Jamestown would back this monster truck over the High Line and claim with a straight face that it’s doing the city a favor by steering clear of the lower mid-block context. Chelsea Market now stands about 70 feet directly above the High Line bed. If built to its full proposed zoning envelope height, Jamestown’s addition would more than triple this, rising about 220 feet above it.

Jamestown’s tower would have a view similar to this, but from hundreds of feet higher up. As part of the Hudson River Park, the small block in the foreground permanently protects the river view. The tower would also have spectacular views up and down the High Line.

What’s this worth? A recent Wall Street Journal article reported that 837 Washington St., a project under way three blocks south of Chelsea Market “could fetch top commercial office rents of $100 a square foot on top floors.” That’s over twice the current average rate for the area’s office space reported by Cushman & Wakefield.

What would Jamestown pay in return? Under a provision extended to only three of its blocks, including the Caledonia site, the Special District’s “High Line Improvement Bonus,” allows an increase in maximum floor area “in exchange for a monetary contribution for the restoration and development of open space on the High Line” and “the provision of . . . High Line support facilities.” (Among the facilities Jamestown has proposed are public bathrooms, although they’re already provided one block away in the Caledonia.) Rather than development of open space, Jamestown’s monetary contribution of about $17 million would be earmarked for future maintenance of the High Line structure. This may not be much at all in comparison to what Jamestown would get back. If these funds and limited spaces are so critically needed by the High Line, as they’ve been described, it raises questions about the park’s management. Why does the brand new High Line already have a maintenance and support-space shortfall? How much sense does it make to close the gap by selling off protected and painstakingly integrated open space? Is this a sustainable plan, or burning furniture in the fireplace to keep warm? If the High Line is that desperate, would it be responsible of the Department of City Planning to approve a fire sale of taxpayer-funded open park space?

Given the contempt Jamestown otherwise shows the Special District’s aims, its contribution smells like a bribe. Buying favor would be in keeping with Jamestown’s promise of jobs to the credulous Tenants Association of the nearby Fulton Houses. In the absence of a real zoning-based argument, what else is left but to build support with handouts? Voices outside Jamestown’s circle of influence are growing. In a community forum on Jamestown’s proposal earlier this month, 11 of 12 speakers from the floor voiced strong objections. The one exception expressed ambivalence. Public officials who would indulge Jamestown’s urban planning charade and ignore Chelsea’s resistance will have much to answer for.

Right across 15th Street from Chelsea Market, vacant and underused lots await development. These don’t offer the top-dollar views to be had from a tower over the High Line, but it wouldn’t take a zoning change to develop them. They could be built upon without devaluing the High Line or marring Chelsea Market, a resource listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places.

Jamestown has cited High-Line-straddling new construction like the Standard Hotel, above, and the High Line Building as precedents for construction above the park, although neither is in the Special West Chelsea District and only one might be considered a boon to the park. The Standard, designed by Polshek Partnership (now Ennead), is true architecture and one of the best recent buildings in New York. Its slim supports and volumes leave much of the rest of its site open, and it is otherwise a special experience to walk up to and under. Built from the ground up on a small block with automatically open exposures, it frames broad views and provides spatial release in ways that would be impossible at Chelsea Market. In comparing its proposed tower design to the Standard, Jamestown only further reduces its credibility.

If anything, the other project Jamestown cites as a precedent, the High Line Building, should be an object lesson. A bulky office tower plopped onto an existing base, it’s a much better preview than the Standard of Jamestown’s Chelsea Market tower. On weekends and evenings when the High Line is busiest, it will be an empty hulk with all the charm of off-hours Midtown. In place of open sky, those seeking escape in a weekend park stroll will see a reminder of Monday morning’s waiting cubicle.

The High Line isn’t the first New York park to be endangered by its own success. Richard Welling’s “If ‘Improvement’ Plans Had Gobbled Central Park” was published in the New York Times in 1918. It shows projects proposed up to that time which would have overrun the Park if they’d all been built, noting that “Many other proposed grabs are not shown in the picture, for lack of room.” Welling writes: “The park was a new institution in 1860, but already it had become apparent that there were plenty of people in New York who saw in this large expanse of ground only room for profitable private enterprise. The Board of Commissioners for Central Park reported in that year that ‘the demands of people who wish to advance their business interests by means of the park are most astounding.’” Welling cites a 1904 scheme by Robert B. Roosevelt, “who wanted to cut up the whole park into building lots.” Zoning-defined open space that’s part and parcel of the High Line can be expected to face similar “grabs” as the park’s phenomenal success enhances its value and attracts the greedy. At a time when the Occupy movement is fighting for the 99%, it should be remembered that the whole point of zoning is to maximize the common good, not private enrichment.

Dept. of City Planning sources: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/westchelsea/westchelsea3a.shtml

More on Chelsea Market:

The Chelsea Market Deal, brought to you by ULURP – November 4, 2012

Is the City Building Google a High Line Skybox? – July 5, 2012

High Noon at Chelsea Market – March 20, 2012

What New Zoning Could Mean for Chelsea Market – May 31, 2011

Saving Chelsea Market – March 22, 2011